Prior to the creation of Collateralized Mortgage Obligations by non-agency institutions, the most common structure was primarily accomplished by GSE’s, who would buy loans from lenders, and then issue pass-through securities. Pass-through securities work just like the name implies, the payments of monthly principal and interest pass through to investors, less a servicing fee.

However, not all investors are treated equally, as some may not have the right to collect any principal, and may have bargained for a stream of the interest only (hence the name IO, or interest only), and some may have bargained to receive payments after other investors, because they bought a security tied to a lower “tranche” of the mortgage pool.

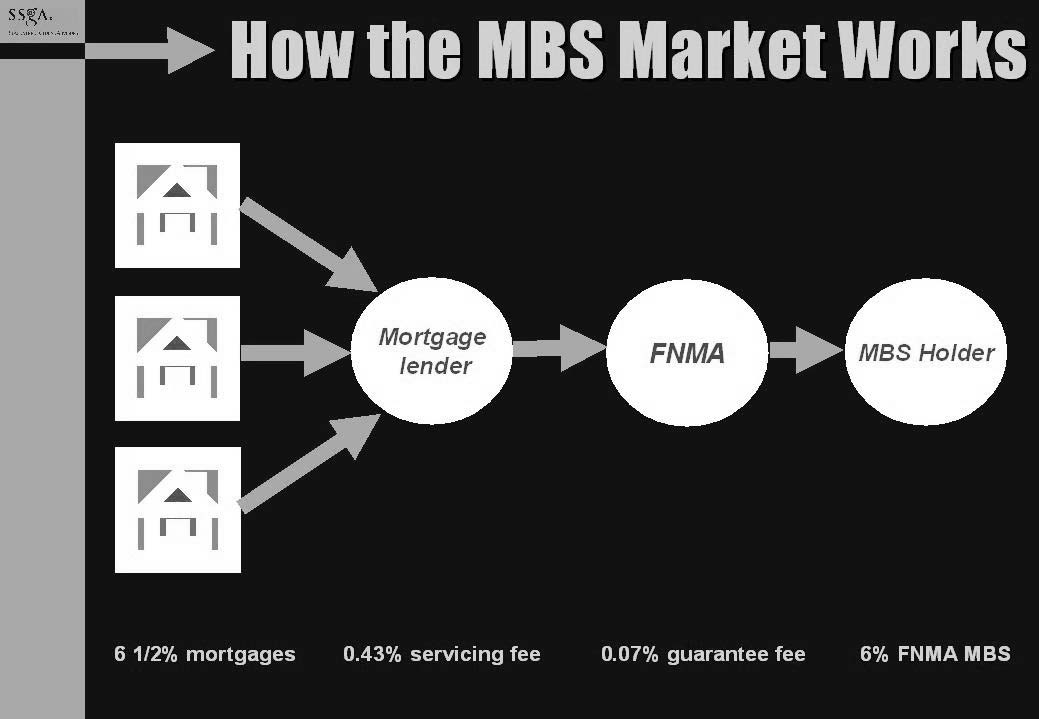

In other words, MBSs are created to pay in a variety of ways, such as interest-only (IO), principal only (PO) stripped MBSs (aka STRIPS). The chart below shows the basic structure of how the MBS passthrough market works:

The oldest, from inception, of pass-through securities are guaranteed by GNMA. GNMA has two primary programs, the GNMA I and the GNMA II. These programs are then further divided into pool types depending on the types and terms of mortgages. The biggest pool is the “SF” pool, which are single family mortgages with 30 year fixed terms.

SF mortgages with 15 year terms are sometimes called “midgets” and are part of the same pool type. Other GNMA pool types include graduated payment mortgages (GPM), growing equity mortgages (GEM), buy-down mortgages (BD) and a famous type of mortgage that caused a lot of trouble in the markets, the Adjustable Rate Mortgage (ARM). Other loans that are securitized by GNMA include mobile home loans (ML), project loans (PL) and construction loans (CL).

Ginnie Mae, is in its whole property of the Department of Housing, and Urban Development (HUD). Hence the timely interest and principal payments of Ginnie Mae pass-through securities are guaranteed by the full faith and credit of the US Government. They have zero-credit risk, therefore which is appealing to investors. The agency does not issue pass-through securities, but instead insures them.

These securities are issued by mortgage bankers and thrift institutions. Many of these institutions join their mortgages in pools of about $1 million. These mortgages bankers apply to the Government National Mortgage Association for their back up and if accepted get a pool number.

Shares of these pools are sold to investors, which in the majority of cases are formed by banks, pension funds, and insurance companies. The minimum purchasing amount is $25,000 which explains why most investors of these pools are institutions. After all pool shares from GNMA are sold securities of the GNMA are negotiated in security markets.

There are a number of Ginnie Mae pools. The most important pools are GNMA I and GNMA II.

GNMA I has fixed-rate 20-to-30 years mortgages with a resulting minimum face value of $1 million, all with the same interest rates. GNMA II pools are larger than GNMA I pools and have mortgages with a variety of interest rates and maturities. There are many different GNMA pools, such as Midgets (mortgages with 15-year terms), GNMA graduated-payment mortgages (GPMs), GNMA buy-downs, and GNMA Federal Housing Authority (FHA) projects.

GNMA I pools are the most homogenous, as they must contain the same type of mortgages and be less than 12 months old. The mortgage interest rates must be the same and the mortgages must be issued by the same lender. The minimum pool size for GNMA I is $1 million.

GNMA II pools allow for multiple issue pools, allowing for a more geographically diverse pool and securitization of smaller portfolios. Issuers are permitted to take greater servicing fees, ranging from 50 bps to 150 bps. The minimum pool size for GNMA II is $250,000 for multilender pools.

Ginnie Mae administers a Real Estate Mortgage Investment Conduits (REMIC) program. REMICs direct principal and interest payments from underlying mortgage-backed securities to classes with different principal balances, interest rates, average lives, prepayment characteristics and final maturities. REMICs allow investors with different investment horizons, risk-reward preferences and asset-liability management requirements to purchase MBS tailored to their needs.

Unlike traditional pass-throughs, the principal and interest payments in REMICs are not passed through to investors pro rata; instead they are divided into varying payment streams to create classes with different expected maturities, differing levels of seniority or subordination or other characteristics. The assets underlying REMIC securities can be either other MBS or whole mortgage loans.

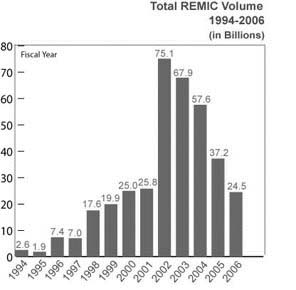

Ultimately, REMICs allow issuers to create securities with short, intermediate and long-term maturities, flexibility that in turn allows issuers to expand the MBS market to fit the needs of a variety of investors (and Wall Street’s desire to create new products). The amount of activity in REMICS increased dramatically over the past few years, as shown in the following chart:

This author suggests that the explosion of REMIC offerings in the last few years presages the an explosion in MBS litigation, because the issuance of REMICs became so widespread, just like when Wall Street took public every dot-com it could during the late 1990’s.

Again, REMICs are a vehicle for creating multi-class mortgage-backed securities (MBS) that resolved certain tax and balance sheet problems related to the use of collateralized mortgage obligations (CMOs). A REMIC is basically a conduit holding fixed pools of mortgages that back securities collateralized by the mortgage cash flows. REMICs can participate in three types of investments:

- Cash flow investments

- Qualified reserve assets

- Foreclosed properties

Examples of these investments include: whole loans; GNMA pass-through certificates; single-class participation certificates; multi-class pass-through certificates; stripped MBS; senior and subordinated mortgage pool interests; and CMOs.

Although a REMIC may have a wide variety of income sources, ownership interests in a REMIC are divided into two categories: regular interests and residual interests. Regular interests are those offered to most investors; they are bond-like instruments with a face value equal to the share of the REMIC’s underlying assets represented by the specific instrument. Regular interests are very flexible in that they can be structured with long or short maturities and also senior or subordinate positions.

In contrast, residual interests collect two types of payments made by the mortgage borrowers: (1) payments in excess of those needed to pay the regular interests; and (2) any reserve funds set up initially that are not needed to make up deficiencies in payments to regular interests. In a REMIC, residual interests are freely transferable. This is an improvement over the prior CMO structure, where the transferability of residual interests is restricted.

The REMIC structure offers issuers a flexible tool with which to design classes (tranches) of interests to meet investor needs and respond to market conditions. Sequential pay (SEQ) classes are the most basic classes within a REMIC structure. They are also called Plain Vanilla, Clean Pay or Current Pay classes. The principal (amortization) on these classes is retired sequentially; that is, a class begins to receive principal payments from the underlying securities only after the principal on the previous class has been paid in full.

The principal payments, including prepayments, are directed to the first sequential class (A) until it is retired, then the payments are directed to the next sequential class (B) until it is retired.

The process continues until the last sequential pay class is retired.

While the class A principal is being paid down, B and any lower class holders receive monthly interest payments at the fixed coupon rate on their principal. Thus, the higher the class, the shorter its maturity (and the lower interest rate it carries, as with all types of bonds). When prepayments are faster than the prepayment speed assumed when the security is issued (or when later purchased in the secondary market), the principal is retired earlier than expected, thereby shortening the average life of the securities bond.

“Average life” represents the average amount of time that each principal dollar is expected to be outstanding. Changes in the average life of the class may affect the yield-to-maturity of the bonds in the class. If the bond was purchased at a discount (below par), the shortened average life will increase the bond’s yield-to-maturity. If the bond was purchased at a premium (above par), the shortened average life will decrease the bond’s yield-to-maturity. The opposite occurs when prepayments are slower than those assumed at pricing.

The Z-tranche or Z-bond is the final tranche to be retired in a REMIC issue. In addition to being last in line for retirement, the Z-bond accrues all of its interest until maturity; in other words, the Z-bond is a zero-coupon bond (hence the name). As the residual class, the Z- bond has one major advantage for the issuer: it permits the REMIC to accumulate a cash flow reserve that is available to retire higher-priority classes if the expected amortization payments and prepayments are lower than anticipated.

Z-bond issues generally have a maturity of 25 to 30 years and are purchased by investors who (1) desire deferred payments; (2) seek a lower exposure to prepayment risk (since longer maturity issues have lower prepayment risks than do short-term maturities); and (3) seek automatic compounding of the periodic interest return. However, Z-bonds carry high risk since they are in a “first loss” position.

Brokers who sold Z-bonds to unsophisticated investors, or those investors seeking conservative to moderate risk, are likely liable for breaching their duty of suitability to the investor and may be liable for gross negligence or even fraud.

Next: Collateralized Mortgage Obligations (CMOs)

CONTACT US FOR A FREE CONSULTATION

Se Habla Español

Contact our office today to discuss your case. You can reach us by phone at 844-689-5754 or via e-mail. To send us an e-mail, simply complete and submit the online form below.